DG MEME had the pleasure to interview Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President of the European Commission and Commissioner for the Digital Market. She is one of the most hard-working and appreciated EU politicians: she blasted Google, Apple, Gazprom, the French and German governments, and many others. Despite such powerful opponents, she always managed to remain impartial and unbiased.

It is every Director-General’s duty to know what their commissioners think, so you can imagine I was very pleased when, at 7PM on a Saturday night, Vestager replied to the meeting proposal I sent her on Twitter: “I really like what DG MEME does, it’s good for the EU to become more relatable 🙂 Just set up a meeting with my assistant”.

I had two objectives for this interview: unveiling the people and the events that shaped Commissioner Vestager; and understanding how she managed to remain clean and motivated in the sometimes dirty and disappointing world of politics. A target that could hardly be reached with the one-hour meeting I requested…

But here we are, with Martina and Rita, my gender-unbalanced wonder team, on the lift to the twelfth floor of the Berlaymont, the territory of Commissioners Vestager, Timmermans, Dombrovskis, Borrell and Hahn. It’s nine in the morning, there is silence in the corridors where collegiality reigns.

We wait a couple of minutes for Margrethe Vestager to arrive. She’s tall and thin, and it looks like she’s floating on the ground instead of walking. Or maybe it’s just her big smile and energetic handshake that confuse me.

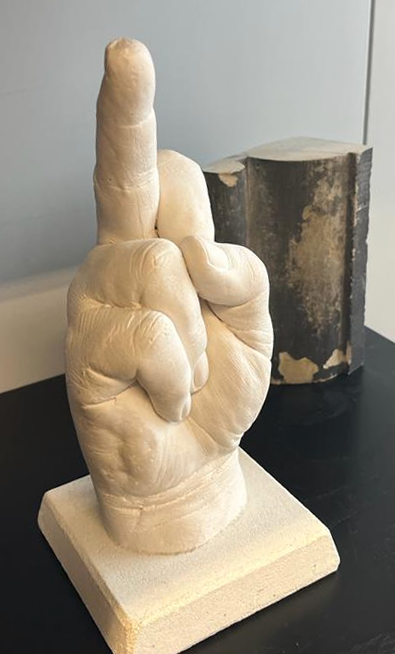

We enter her office, which is full of paintings and souvenirs, including the famous middle finger. It was a gift from the Danish trade unionists, displeased with some of her ruling on state benefits; “It reminds me that my decisions will never make everyone happy”.

We sit at the table; the tea is boiling while Martina unpacks the amazing chocolate cookies she baked for the occasion; the sun unexpectedly filters through the clouds and the shades, giving a warm touch to the room. We break the ice talking about cooking and recipes. We reach an acceptable level of hygge for the interview to start.

You grew up in Ølgod, a small railway town in Denmark, what was your dream job when you were little?

Well, I never wanted to be a politician and I also never dreamed of working outside Denmark. I wanted to be an engineer, because I love bridges and I thought that constructing bridges is the greatest thing you can ever do.

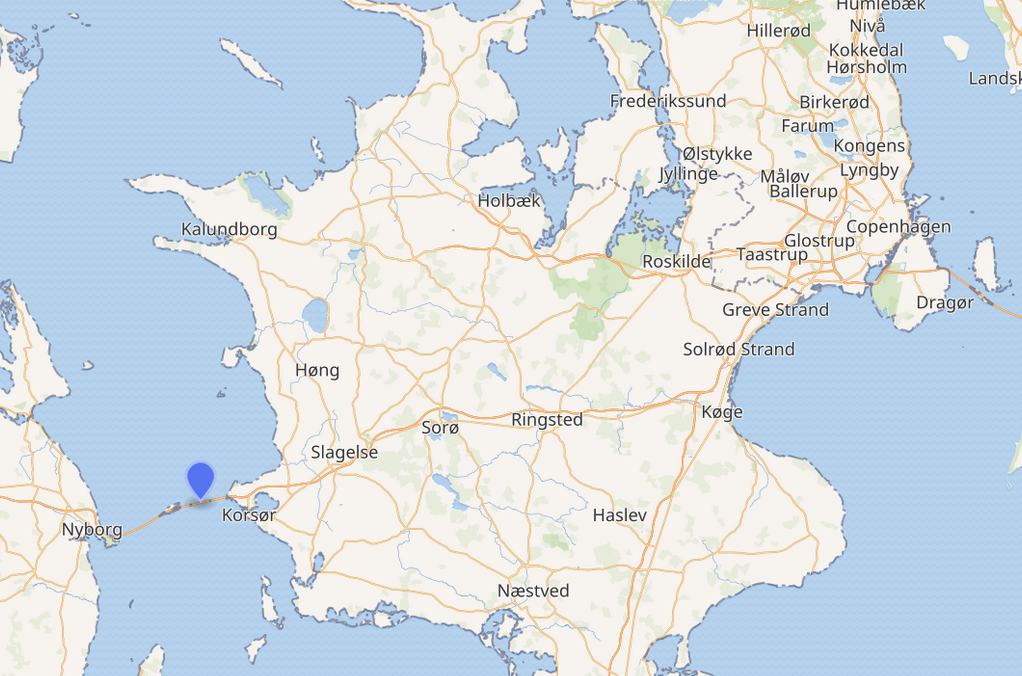

The Great Belt Bridge or Storebæltsbroen (violet pin) connects the towns of Korsør and Nyborg. The first project was drafted in 1850, its construction was approved in 1978, it started in 1988 and ended in 1998. So don’t complain about EU efficiency.

Physical or social bridges?

Physical, physical. When I was young the Danish government finally agreed to build the Great Belt Bridge and it took more than a 100 years to make that decision. This made me think that they would never build any more bridges in Denmark again, so I dumped the idea of being a civil engineer. I was, of course, completely wrong, but then I made other choices and here I am.

Going back to your family, your parents were both Lutheran priests. How much do you think their ethical view and work, for example their involvement in the Dansk Santalmission, shaped your views on what is right and what is wrong?

The truth is that you don’t really think about ethics and values when you’re growing up into it. This was simply my life, my everyday life, you know. For example, this Dansk Santalmission, the point was not to get as many baptized people as possible; the point was to help them to be independent and if they then wanted to, they could be baptized. Long before micro-financing was ever a thing, they would enable women with sewing machines to use their skills and make clothes, thus creating a market and generating some income.

You don’t meet people with the theory of Jesus and Christianity, you meet people with, “How can I help you to help yourself?”. In Denmark we were collecting money to fund this mission. When I was small, I was allowed to go with my dad when he had to travel all over Denmark, contacting this sort of NGOs, mostly run by women, who were knitting and crocheting all through winter. They would then organize some sort of bazaar, where you could buy all these products and also the stuff that came back from Bangladesh, such as clothes, tea and candles, to support the mission.

The big history, helping people that lived far away, was so intertwined with your personal father-daughter history that you didn’t even realize the difference?

One could say that. The best part was that when we were going back home late at night, my father would open the songbook on the steering wheel and sing us home, because otherwise he would fall asleep; and we also had this agreement that if he was smoking cigars in the car I could have sweets.

That’s how you learned the art of negotiation?

Haha, exactly.

I assume they were kind of busy parents?

For sure. When my dad got his job in the church, they didn’t have office hours, their house was open all the time. So people were coming in at every hour: children were born, parents died, somebody needed someone to talk to… There was no division between their working hours and their life as such, it was completely woven together.

Just like a commissioner’s life?

Ahah, I guess.

Nevertheless you said that you do trust religions but you don’t trust churches. So you witnessed the positive changes that people can bring when they are in small groups, but you are suspicious of the church as institution?

Yes, somehow it seems to me that when a religion gets organized, very rarely things go well; after all, lots of people have been killed in the name of religion. For me it is just important to believe in something bigger, otherwise I think I would feel alone.

You consider yourself religious?

Yes, I would say that.

If the head and the heart and the stomach agree, then I know I am taking the right decision.

A moral compass is for sure useful when you are in power… You mentioned that when you take these huge decisions, that influence thousands of people, you just “feel this is the right thing to do”, giving almost an artistic twist to your work, not unlikely an artist that thinks: “This painting is beautiful, this painting is true”. Can you describe this feeling?

Well, before that moment, before that feeling of ‘doing the right thing’ comes, there is an incredible amount of work by many, many extremely dedicated people: from the very early days of any case information is gathered, analyzed, and discussed. When it comes to me, when it’s my responsibility, because no matter the advice I get it’s my ultimate responsibility, if the head, that has been following all the case, and the heart, that has been steering the work, and the stomach agree, then I know I am taking the right decision.

And how do you keep all this work and information together?

Well, we talk a lot about things here, people give a lot of presentations in person. Because when people are responsible for a case, they want to talk about it, and this conversation helps working on a case as a team. And the hierarchy supports the team and the communication, because we know that paper can hide everything, if there is no conversation behind it.

Words of wisdom! Let’s go back to your story. You entered politics in 1989, which was also the year the Berlin Wall fell. How do you remember it?

Before the invasion of Ukraine, I thought the fall of the Berlin Wall would be the biggest thing I would ever experience, because we never saw it coming: I was brought up to think that the Cold War would just last forever. No one, no one questioned it. So when it actually happened, it was a shock: amazing things can happen if people want it!

In my team we know that paper can hide everything, if there is no conversation behind it.

Did you realize how important the Fall of the Berlin Wall was for the whole European project?

No, not at all. But it was just amazing to see people who had no freedom being able to go where they wanted, it impacted us all. I remember this official visit in Vienna with Věra Jourová, during the Austrian Presidency. We were waiting for the president and we were looking down in one of the courtyards and Věra said: “I was there when the Wall came down, I had borrowed a car from a friend and I just took my boy with me, who was three at the time. We had no money, but we wanted to experience the feeling of being able to leave Czechoslovakia. I felt, if I can do this I can do everything”. And that was pretty much the sensation we got at the time: anything can happen!

Do you have any recollection of that day? Where were you?

At the university, on the 10th of November, the day the Wall actually came down. We had these big TVs that you could sort of roll out and we had them in the main halls, so that everybody could see what was happening.

And you were twenty-one at that time. And just a few years later you came to Brussels as trainee?

Yes, it was in 1991, I had met my husband…

Wow, during the traineeship?

No, no, he was studying in Paris, at the Sorbonne. And I was here, a trainee at the European Parliament. It was a very, very different parliament, back then, it was not like now, in full power.

Full power, that’s very cute, some might say we could have it in even fuller power…

Well, let’s say I’m old enough to appreciate the change: now they pass resolutions on everything, back then it was so much weaker. And I remember my frustration, you know, piles and piles of paper everywhere and a lot of energy going into resolutions and very little impact.

Were you allowed to go to Strasbourg?

Once! And it was the time of the boxes, you know, you could hide a corpse in those boxes and no one would find out. It was just papers and papers and papers that were traveling in trucks and lorries, it was a gigantic operation every time. So actually I was a bit reluctant to join that carousel, also because I just had my luggage stolen in a tram in Brussels and I was still a bit shocked.

What was in that suitcase? Anything you can tell us?

Many things that had an emotional value to me: the suit that I sewed myself…

You made your own dress? Not only knitting, this is haute couture!

Ah, of course, I can also sew my own clothes. And I also had a very nice, very expensive pair of shoes, with a sort of a silver thingy on top. You know, I treated myself to these expensive shoes; and a necklace, that I inherited from my grandma. I was carrying all that because, you know, I was a trainee at the Parliament, so I wanted to give the best impression.

And I was there, sitting in the tram, just some stranger and me, and when the tram stopped, he just got up and grabbed my bag. And initially I ran after him but I didn’t dare to pursue him, because he was a big guy. So I was a bit disappointed with Brussels.

I can imagine, from time to time we all are.

And keep in mind this was before they got in control of the garbage in the streets.

Oh, are they now?

Oh, there’s a great improvement, a great improvement! Now Brussels is clean and nice and well functioning, but back then there was garbage in the street all-the-time.

I was a bit disappointed with Brussels, but this was before they got in control of the garbage in the streets.

(no, she was not joking)

What motivated you to become a trainee in a weak Parliament, when you already started your political career in Denmark?

Oh, I already had a strong interest in Europe. I had been very engaged in the campaign for the Single Market in 1986 and I loved the idea of moving to Brussels. I just didn’t feel that Brussels loved me back.

Ah, we all had that feeling sooner or later…

It was a tough relationship, at the time, but I didn’t want to give up on the idea. So, I kept working on it.

How did you perceive the whole moving to Strasbourg thing?

I found it absolutely crazy, I remember that day, I was just being appointed commissioner, and I was with my family and friends in a farm in the countryside. My father was seventy, I think, and the first thing he told me when I announced I was going to move to Brussels was: “Can you then stop that ‘going to Strasbourg’ thing?”. Yeah, that was that, out of the top of his mind.

And I was so happy to learn that the Parliament has done everything they could. But then France took them to court, making life difficult.

What was your first impression of Brussels? Did you fly here or did you arrive at MIDI?

I don’t remember it very well, but I definitely came by train; and I found it a mystery, it was so difficult to find your way around. You really have to think hard to understand that Brussels is not a grid, there is no logic, because you have all these squares, which are not squares, because they are star shaped and this means that there are no parallel streets. So if you get a wrong turn, you just end up in a completely different area.

But when I then discovered the system of the slim sort of city houses and that it’s a city that is so unsentimental, anti-authoritarian, then you know, it really grew on me. During the pandemic, of course, I had much more time to discover the city and its rhythm, its weird harmony.

What do you like the most about Brussels?

Its diversity! Seeing all kinds of people every day. I live in Ixelles and everyone, everyone is living there. You know, low income, high income, small families, big families, single people; and from every corner of the world! And I think everyone feels welcome.

And what is one thing that you hate the most about the city?

Traffic, I don’t feel safe biking here. I know more and more people do, but coming from Copenhagen, where you have dedicated bike lanes, when you come here and you see that they have painted something on the street, you think: “You call that a bike lane? That is not a bike lane, that is just the part of the road that used to be for cars”.

So, how do you commute to work?

I walk, it’s more relaxing.

Talking about relaxation and focusing methods: your knitting habit became some sort of a EU topos already… Why do you knit elephants?

Because I stumbled upon one little elephant ten years ago and I liked it. I think elephants are very nice animals. They live in groups, they’re lead by female, they’re very social. They remember kindness, and they remember hostility as well; so you can become friend or also enemy of an elephant.

And what are you working on now?

Right now? On a sweater and pants for my grandson, he was born a few months ago.

Who taught you how to sew your own dress?

It comes from my grandma. When I was a child, we were spending together these long summer days together, and she would allow me to use her sewing machine. I could do everything I wanted, and I felt free with her.

Was your grandmother a role model for you?

Yes, she was amazing! She was a teacher, but she had a hearing deficit, so she was teaching smaller groups. specifically children who had problems reading. The passion she put into making sure that these children had confidence and that they got a job after school was inspiring to me. Also, she knew everybody in town and she was friends with everybody.

Talking about friends, is it easy for a politician to make real friends? You know, people that you can be yourself with, without fearing that they’re going to leak to the press everything you say.

Well, friendship can be a tricky thing, but I think it doesn’t make sense not to trust people. If you feel that you like the other person, then you need to trust them as well, otherwise you cannot develop a relationship. And if you get disappointed, well you learn from that disappointment.

Friendship can be a tricky thing for a politician, but I think it doesn’t make sense not to trust people, otherwise you cannot develop a relationship.

What about friends that you make on work? What is the nicest event you remember?

Oh, we had this conference on Making Markets Work for People and we had the nicest dinner. I had Kristalina Georgieva on one side and Nadia Calviño on the other, and it was really nice, because we had some serious talks about feminism and leadership and the economy.

Mrs Georgieva was Commissioner for Crisis Management and International Cooperation under Barroso; and Budget Commissioner under Juncker for two years, before quitting the job to become Chief Executive of the World Bank Group. Does she vibe with your view of leadership?

She is one of my heroes, she’s so good. I’ll never forget this story she told me about her graduation. It has been very hard for her to reach that milestone, because the authorities didn’t like some protest songs she had written and they were making lot of problems for her. Finally, on the day of her graduation, she had brought home a bottle of cognac, which was really difficult to get in Bulgaria back then. So she was there with her parents and they were just about to open this bottle when an earthquake came. And she told me: “I still feel ashamed to this day, because I didn’t just put the bottle down and run to my parents. I also saved the bottle”.

A question from one of your biggest fan, Costina, who would really love to be here with us today. Do you listen to the radio and if so which stations?

Yes, I follow the Danish radio, I like to hear what is going on back home, because my family lives in Denmark and I go home to Denmark quite often. So I want to be part of that. I also listen to BBC World. I think it’s very good because it brings you news from everywhere, and it helps me keeping an eye on important events that still wouldn’t make the headlines in Denmark.

Do you feel a difference in style between British and European media?

There is a huge difference, yes. I’d love to have some sort of European morning news… I used the Euronews app, of course, but we’re still not there yet. Our news are always local: the French, the German, the Danish…

It’s probably hard to break the linguistic differences…

Well, this kind of English we speak in the EU is our Esperanto, and maybe the European news could be in that language for a start.

Do you think that kind of English is the EU language right now?

I definitively think so. I had never worked in English before, so when I came here the first three months I was completely flat-lining when I got home. You know, I had to figure out: do I know what I’m saying right now? Does my counterpart know what he’s saying right now? And do we understand each other?

My British colleague back then was Jonathan Hill (the European Commissioner for Financial Stability, ed.) and I asked him: “Aren’t you just devastated listening to how we treat your language?”. And he replied: “Well, I’m so honored that you’re all trying”

“I choose to be late, so the College can gossip a bit”

Margrethe Vestager and Jean-Claude Juncker, former Commission president

The problem is that when you don’t speak a language very well, you also lose your sense of humor. And I didn’t like that. So I tried hard to master that language, so that I could regain my sense of humor.

So you agree with the theory that one has different personalities when speaking different languages?

Yes, I have no doubts about that.

Talking about languages, how easy is the communication in the College of Commissioners? How do you cope with different cultures, different accents and different English knowledge?

Well, the president is always leading the meeting. With Juncker we had a bit of time to socialize, because he would come a bit later than agreed. Ursula is more on time, so this leaves less time to socialize.

After the president’s introduction and the main points, there are different presentations or orientation debates. The French and German colleagues speak their respective language, actually. But I think the rule should be that you can speak French or German or English as long as it’s not your mother tongue, so that we would all be on the same level.

How long do these meetings usually last?

It really depends on the matters discussed. Sometime they can last hours, other times they’re quite quick.

Cool, I see Paola is waving the “time is up flag”. One last personal question: you were a smoker for a long time, is this correct?

Yes, I see you did your research!

Ahah, yes, we’ve been working on this interview for weeks. So, when did you start smoking? And why?

I was fifteen, I had this friend who suggested that we should try it.

And then it felt good?

No, it didn’t.

So the first time was just peer pressure?

I guess. It really didn’t taste good. But since we were not allowed to smoke, because we were too young, it tasted much better.

And why did you stop?

Because we were discussing starting a family with my husband and he told me: “We can do that anytime, as soon as you stop smoking”.

A clear message, no room for negotiation.

Quit smoking was really thought-provoking for me. It was very popular to use those patches and when I felt the nicotine entering my skin and calming me down, I realized that I didn’t want to reach such a level of addiction.

“I became minister”

No relapse into smoking?

Just once, after a 5-6 years break.

Any stressful event that made you go back into smoking?

I became a minister.

Understandable. And yet you managed to quit smoking again?

My family helped me, my husband said: “Listen, we want you to stay, could you please stop smoking?”. Somehow it’s not enough to read that smoking is dangerous in a pamphlet in the doctor’s waiting room; it’s the feelings and the emotions of those around you that make you realize you’re hurting yourself and those that care for you.

“If you want to snap a few pictures together, it’s now or never”, says Paola with a smile, “We have a minister up next”. A persuading line, we wouldn’t want the minister to wait. We still have so many questions, but we’ll leave them for the next time.

By the way, I am sorry for the way I mispronounced your name during the interview. What is the right pronunciation?

It’s ˈvestˌɛˀjɐ. But don’t worry, I have settled on the idea that if they can recognize my name in writing, I’m happy. So they say: “Ok, I saw that woman already and now she’s here again”. And I appreciate when somebody makes the effort to learn the pronunciation. I try to pronounce people’s name in their original language too, and I fail consistently.

A big thank to Paola, for helping organizing the meeting; to Camilla for the precious Danish culture clarifications; to Martina and Rita, for the support before, during and after the interview; to Anna and Antonis for proof-reading the draft; to Laura, for the most secret tip; and to all the photographers I stole the pictures from, I hope you’re fine with that, otherwise let me know, I can also add credits, in case.

1 reply on “Memories of a Vestagiaire”

Really amazing interview! It is genuinely so nice to get a personal insight into the lives and politics of such important people to European politics, and even the people mentioned in passing here are really humanised (Jourová in particular). It is really commendable that Ms Vestager agreed to take some time out of her day to do this, and it would be amazing to see more interviews with the Commission!