I started reading about Greenland after it made the headlines a few months ago, and I found it very fascinating: it is one of the biggest countries in the world, but it has less than 57,000 inhabitants; Greenlanders are EU citizens through their Danish nationality, even if Greenland left the European Economic Community in 1985, partly because of concerns over fishing rights; Greenland is an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark, and it is on its way to independence since 1979, even though only a few of the political and legal competences have been taken over by the Greenlandic government from Denmark.

Add to this that global warming will (sadly) open up new trading routes and mining opportunities, and you get a wonderful geopolitical puzzle and a diplomatic limbo, that can’t but spark the curiosity of a traveler like me. So I decided to come up here and see what is happening, also because on the eleventh of March there will be the political elections of the 31 members of the Inatsisartut, the Greenlandic Parliament; and this might have interesting repercussions on world politics.

Greenland is a wonderful geopolitical puzzle and a diplomatic limbo

The plane from Copenhagen is on time: we reach the skies over Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, after 4 hours and 30 minutes. But we do not land, we keep circling over the airport for almost one hour. After that, the captain makes an announcement with a disgruntled voice: “As there is a snow storm over the airport, we can only keep flying over it for one more hour. After that, we will have to fly back to Copenhagen”. All the passengers start looking nervously at their watches: 10 minutes, 20 minutes, 25 minutes… Finally, 45 minutes after the announcement, we get the green light from the control tower and we land happily (double round of applauses for the captain).

I got off the plane in an atmosphere very similar to John Carpenter’s The Thing: a pale sun is visible through the clouds, a strong wind carries snow and ice, the thermometer reads -18°C. I hurry up to reach the entrance door.

The airport of Nuuk is brand new: the route from Copenhagen opened in winter 2024 and the one from New York should open in summer 2025. The Danish government quickly approved a loan for its construction, after China showed interest in doing the same. The bus to the city goes every hour and its ticket is the only item I had to pay in cash in the whole trip.

My cozy hostel is located just a few minutes away from the Nuuk Center, the largest and tallest building in Greenland (8 floors!). In a radius of two hundred meters from it, one can reach the Katuaq Culture Center, the Greenlandic Parliament, the government offices (located in the Nuuk Center), and the one of a kind European Union Arctic Office, which is not a Representation (Greenland is not part of the European Union) nor a Delegation (Greenland is part of a EU member state).

As my objective for the trip is meeting locals, I decided to volunteer at the yearly Snow Festival of Nuuk, a friendly three days snow sculpting competition. The atmosphere is relaxed and it’s easy to make new friends:

“In Greenland, many people still take pride in hunting their own food. When you rent an apartment here, among the specs, you’ll find the amount and size of fridges it contains”, twenty-five years old Ivik explains me. I learn that anybody, even children, can buy a gun in Greenland and that a reindeer can provide enough meat for a few weeks.

While traditional hunting is still common, the Greenlandic fur and seal meat industry was hit hard at the end of the Nineties, when PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) campaigned against commercial seal hunting, lobbying the EU to introduce bans on large-scale commercial hunting practices.

The conversation does inevitably move towards the recent statement of President Trump about the US intention to buy Greenland from Denmark. I ask Ivik how he feels about seeing his country in the world headlines. “Quite angry, to be honest. It seems that for Trump my country is like a pair of boots that you can buy in a shop”.

“It seems that for Trump my country is like a pair of boots that you can buy in a shop”.

People still remember the recent speech of Donald Trump Jr., who visited Nuuk “as a tourist”, a few days after his father announced the desire to acquire the country. The Greenlander support for joining the US is quite low (3% of the women and 8% of the man) and it seems that Trump Jr. paid some homeless people to come and listen to his speech. Igaliko, an IT technician that studied in Copenhagen for three years and is now back in Nuuk, adds: “We are aware that among the Inuit people living in other countries (like Alaska and Canada, ed), we have the best living standards and self-determination, and we don’t want to lose that”.

Almost every Greenlandic politician supports the country’s independence desire, but there is no shared vision on how and when this should happen. At the beginning of 2024, Prime Minister Múte Bourup Egede said that “work has already begun on creating the framework for Greenland as an independent state”, hinting April 2025 as a potential date for a preliminary independence referendum. An enthusiasm that was weakened by Trump’s wish to “get the country, in one way or the other”: in January 2025, Egede stressed the importance of the support and cooperation with the Danish government, stating that Greenland has “no desire” of becoming part of the United States, though the “doors are open in terms of mining”.

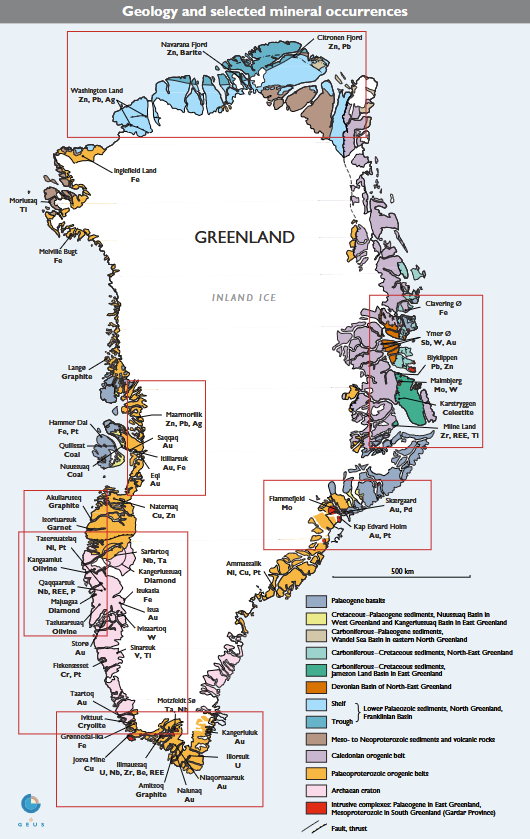

“It is true that we rely on Denmark for the goods and equipment, but this might change if we find the proper way to exploit the valuable metals hidden deep underground”, a student of mining technique tells me. Mining was a hot political topic in the last elections: while most parties agree on welcoming mining companies, only a few of them agreed on mining uranium.

The earliest recorded mining activity in Greenland began around 1782, when coal was extracted near Qaarsut, in northwest Greenland. By the mid-19th century, Greenland’s mineral potential gained attention with the discovery of cryolite, a rare mineral used in aluminum production. This was the topic of a documentary published by the Danish national broadcaster DR, which has reignited discussions about the Danish exploitation of Greenland: in the whole chain of extraction, preparation, shipping and reselling, Denmark made significant profits, while the local population received very minimal economic benefit. The documentary, titled Greenland’s White Gold, was taken down by the broadcaster, claiming that the figures of the profits were exaggerated and misleading, which is still subject to debate.

“We don’t see any proof of Russian or American influence in these elections, but I doubt they could have done a better job than DR when they chose to remove that documentary”, a Danish journalist tells me in front of a beer at Daddy’s, one of the few local pubs. “It suggests that Denmark has something to hide, supporting the most radical pro-independence parties. It was a blow for all the politicians, NGOs and reasonable people working on a better cooperation with Greenland. This plays right into Trump’s hands”.

“We don’t see any proof of Russian or American influence, but I doubt they could have done a better job than DR when they chose to remove that documentary”

According to the journalist, Trump’s obsession with Greenland can be explained by three factors: territorial gain is part of his rhetoric, people in his entourage own mining companies, and the island is in a strategic position (the name of the capital also sounds like ‘nuke’, which might arouse his subconscious, ed).

The US military presence in the country dates back to World War II, when nazi-occupied Denmark allowed the US to land military planes in Greenland, in order to prevent a nazi invasion. The US already tried in 1946 to buy the island from Denmark, in exchange of 100 million Dollars in gold, but the offer was turned down. As the US and Denmark are both part of NATO, Denmark let US troops stay and, after signing a Treaty on Common Defense of Greenland in 1951, the construction of the Thule Air Base (now known as Pituffik Space Base) began.

An old lady, who may have had one too many, asks to join our table. She speaks a few languages and she seems curios about our opinion on Greenland. “You Europeans, you think you are so civilized, ah!”. “You don’t feel European?”, I kindly ask. “Europe is far, America is far, everything is far from here. We would just like to be left alone”. “I’m afraid this is not possible in our interconnected world”, the journalist points out. “I know, in the Fifties we welcomed electricity and heating and roads… But we did not know it would change our way of living so deeply. Things were simpler back then”. And then she leaves, greeting us with a dramatic flourish. In vino veritas, they say.

Trump’s obsession with Greenland: territorial gain, strategic position and his advisor owning mining companies

Back to the hostel, I meet Anja, a Greenland-born, Greenlandic-speaking music teacher, who has been living in Denmark for more than ten years. I ask if she came back to vote, but, to my surprise, I find out she is not allowed to: as there is no legal definition of Greenlandic nationality, only people with Danish nationality who are resident for more than six months in Greenland are allowed to vote.

There have been talks about creating an ‘Inuit register’ to exclude the Danes, but this would be technically very difficult. “Love finds a way where politics fails”, says Anja, “most Greenlandic people, just like me, have both Inuit and Danish ancestors”. A good answer to the head of the Greenlandic nationalist party Naleraq who claimed that: “The people who colonized the country are not supposed to be allowed to decide whether or not they want to continue colonizing”.

Sunday comes and Sofia, a local couchsurfer I met at Katuaq, has the time to take me on a Nuuk-tour: we start with a breath-taking walk along the coast, with stunning views on the little icebergs floating calmly in the icy sea.

“Europe is far, America is far, everything is far from here. We would just like to be left alone”

“See that yellow house with the red roof? It belongs to Svend Hardenberg, the actor who plays the Greenlandic Foreign Minister in the Danish political drama TV series Borgen. He was initially a political advisor for the authors but when they realized he could act, they offered him the role”.

We then reach the panoramic hill on which stands the statue of the Dano-Norwegian Lutheran missionary Hans Poulsen Egede, who “founded” the city Godthaab (“Good Hope”) in 1728, in the area of an Inuit settlement called Nûk (which means “cape”). The name of the city was reverted to Nuuk in 1979, when Greenland obtained home rule and the competence to define the names of its places.

Egede spent many years living with the Inuit people, studying their language and converting them to Christianity. According to a popular anecdote, he had to adapt the Lord’s Prayer as ‘Give us this day our daily seal’, as Inuit did not have a word for bread. Egede’s journey marked the reconnection of Europeans with Greenland, which was lost for over 300 years, since the time the Norse left the island for unknown reasons; it also paved the way to the Danish colonization of the island, and for this reason Egede’s figure is controversial.

We have lunch at Unicorn, a very good restaurant that serves a fancy version of the local food, like snow crab and whale. We debate whether whales should be considered meat or fish with a friendly waiter. I decide not to calculate the bill in Euros, a wise approach when traveling in any Nordic country: it is better to have one shock when checking the bank balance at the end of the trip than many little strokes every day.

As it is still sunny, and the golden hour is coming soon, we decide to do a small hike, reaching by bus the airport and from there the top of Quassussuaq (Lille Malene in Danish, 440m above sea level). The view of the Labrador Sea and the glaciers and the icebergs is wonderful. Sofia points at the main landmarks of the town: the old and new harbor, the airport, the university and the new prison: “Imagine the pain of being imprisoned in a cell with such a view”.

The prison made the headlines in July 2024, when anti-whaling activist Paul Watson, co-founder of Greenpeace, was arrested in Nuuk, under an international arrest warrant issued by Japan. He was accused of confronting a Japanese whaling vessel, with charges that could result in a 15-year prison sentence. French President Emmanuel Macron actively opposed Watson’s extradition to Japan, while filmmaker James Cameron and primatologist Jane Goodall advocated for his release, which happened after 150 days in preventive detention.

Back at the hostel, I meet Akimiu, a fifty-five years old carpenter from Sisimiut, a city 300km north of Nuuk. He is in town to look for a job and he is curios to know what brings me to Greenland. His English is basic (“I learnt it when I lived in Copenhagen”), but we nevertheless have a friendly chat over two cups of niitsit, the Greenlandic tea, that Akimiu corrects with a few drops of Isfjord gin. We discuss music, (he is also a great fan of rock), and he mentions the Greenlandic band Sumé, a cultural phenomenon back in the days.

The rock band was formed in 1972 by Malik Høegh and Per Berthelsen in Sorø, Denmark. The name “Sumé” means “where?” in Greenlandic, reflecting their questioning of Greenland’s cultural and political identity under Danish rule. Their work, rooted in the anti-imperialist movement of the seventies, sparked a cultural awakening that contributed to Greenland’s Home Rule in 1979. The fact that the lyrics were sung in Kalaallisut (West Greenlandic) was already revolutionary, considering that in those Danish was the most used language in Greenland.

The Greenlandic rock band Sumé, whose lyrics questioned Greenland’s cultural and political identity under Danish rule, contributed to Greenland’s Home Rule

Now I have a new soundtrack for this trip, and I particularly like Inuit Nunaat (the Country of Man, or Greenland) and the instrumental Ode Til Heimaey, with its Lynyrd Skynyrd inspired riff.

I go back to Katuaq, where the sculptures are taking shape. Walking along the exposition path, I observe with admiration the artists that work hard on the snow with different metal tools; some sculptures are abstract, some figurative, some others can be accessed, like a small house, an igloo and the head of a woman that has a slide in her hair.

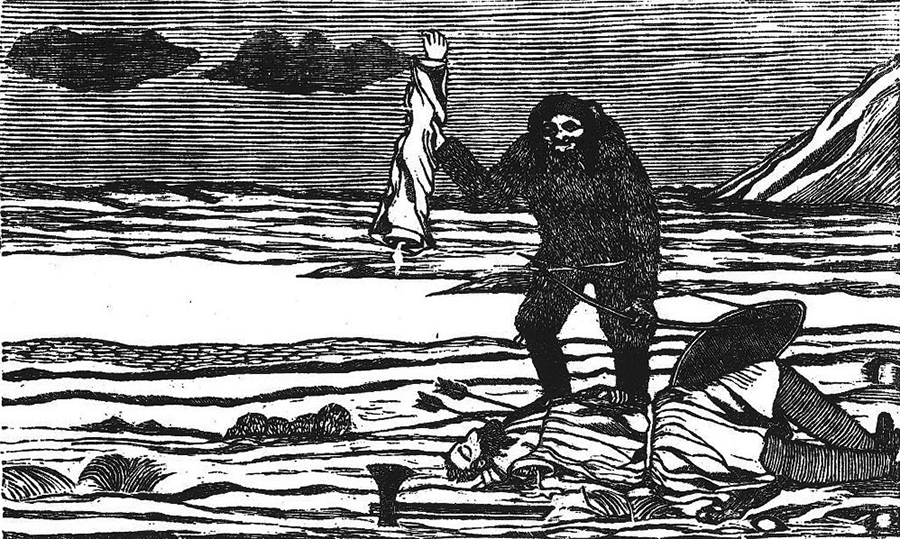

“It represents Sedna, the Inuit Goddess of the Sea”, explains Pipaluk, another volunteer. “When she is angered by men, she can trap the sea animals in her hair, causing famine. As her father chopped her finger off after she refused to marry, she is unable to comb her own hair and a shaman had to do that for her”.

Other local volunteers know a different version of the story and there is a beautiful exchange of details about the myth and its sources, and about how practical it would be to have a God that protects our ecosystems…

The aurora paints green hues on the black sky; and the stars look down.

Note: as Nuuk is a city of only twenty thousands inhabitants, the name of the people I met has been changed to protect their privacy. Similarly, some dialogues have been combined for narrative purposes.

2 replies on “Elections on thin ice – a Journey to Greenland, the Outpost of Democracy”

Excellent piece combining personal & lived experience, contextualised history, complexity & accessibility, facts and anecdotes. This deserves a wider audience.

Thank you, interesting to read!