Kaja Kallas has been high on my list of cool people to meet for a couple of years. Not only did she inspire lots of memes, but she also retweeted some of them when she was Prime Minister of Estonia. It felt very natural to talk to her: she has a very direct communication style and a great sense of humour, as the genuine and colorful pictures on her social media accounts show. I am happy to share with you some excerpts of our conversation, offering a sneak peek of her life and the changes Estonia went through in the last decades.

“Oh, so you are DG MEME!”, I’m glad she recalls my page, as I enter her office at the fifth floor of the European External Action Service. “There was an error in your meme about Estonia”. It hurts, but she is right.

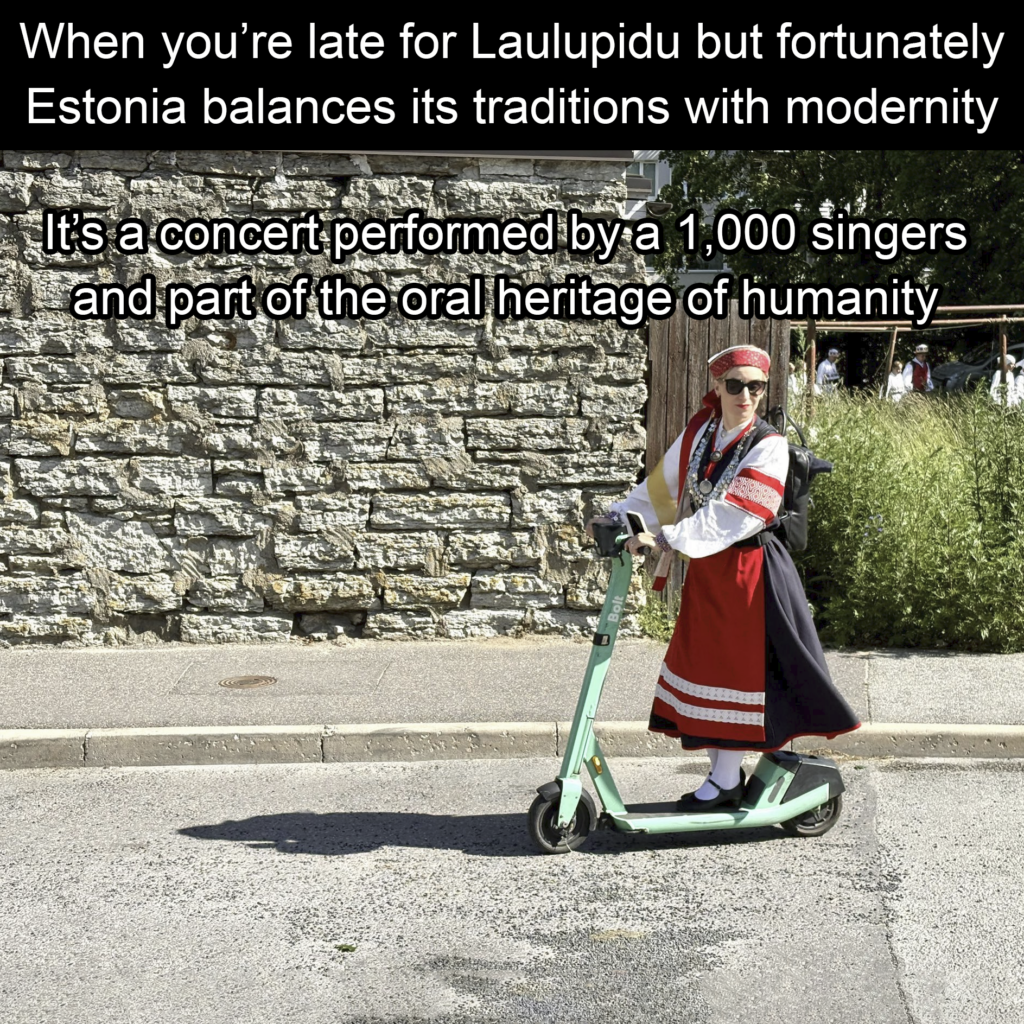

Her voice is hoarse as she is still recovering from singing along with the choirs at Laulupidu, the Estonian folk and dance music festival, held once every five years in Tallinn.

“You sit on a wooden chair, listening to all these choirs for seven hours; it’s fifteen degrees, it’s pouring, but you don’t feel it, you don’t notice it, because the concert is just amazing.”

Laulupidu is a powerful expression of Estonian national identity, which communicates a strong feeling of belonging and pride. Estonia, the smallest of the Baltic Republics, has a population of 1.3 million, and a sizable Russian-speaking minority (about 30%), that moved in during the Soviet times. This festival reminds people how singing played a central role in restoring Baltic national sovereignty, giving a message of hope to the countries which are still oppressed by Russia.

“Usually, Estonians don’t really talk to each other much; but at Laulupidu the atmosphere and the music change people and everybody is friendly, helpful and in a good mood.”

Kaja Kallas grew up in Lilleküla (“the Flower Village”), a residential district on the western side of Tallinn. Her mother, Kristi, was deported to Siberia as a child. On her return, she studied medicine and worked as pediatrician. Her father, Siim, studied economics and worked as finance consultant. He gained popularity as conductor of the Sunday morning radio quiz show Mnemoturniir.

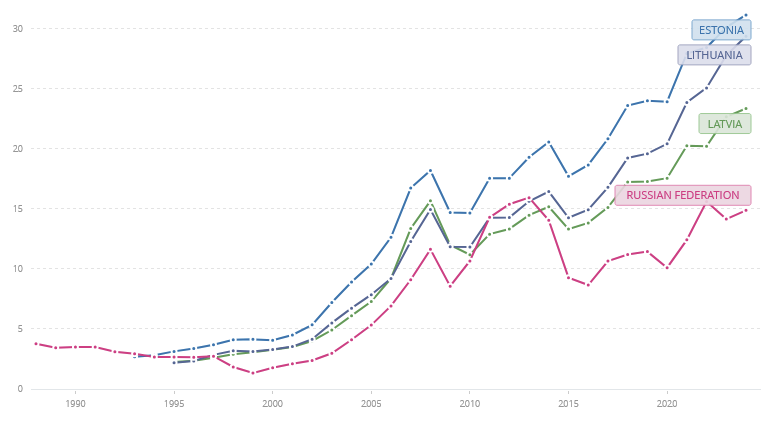

Taking advantage of the increasing political freedom at the end of the Eighties, Siim developed the Isemajandav Eesti plan (“Self-managing Estonia”), with the aim of making Estonia economically independent from the Soviet Union, adopting a market economy, an re-establishing Estonia’s own currency (the Kroon) and tax system.

“It was fascinating, they had this big group of people debating all these topics and improvements. I remember the discussions happening in our kitchen and I really liked listening to them. In the end, only four of them had the political courage to sign the proposal, as it was going completely against the Soviet Union’s diktats. They also feared being arrested; fortunately, Gorbachev was already in charge and nothing happened.”

When Kaja was twelve she participated with her family in the Baltic Way, a peaceful political demonstration in which approximately two million people from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania formed a 600-kilometer human chain to demand independence from the Soviet Union.

“I was spending the summer with my brother at my grandparents, next to Viljandi, that’s where we joined the Baltic Way. My grandparents resettled there after the deportation. Before that, they were living in Abja-Paluoja (South Estonia, close to the Latvian border, ed), but the rule was that, after being deported, you couldn’t return to the place where you had your home.”

The memory of the Soviet occupation is still vivid in Estonia: in 2018, President Kersti Kaljulaid unveiled the Memorial to the Victims of Communism, built just in front of a monument from the sixties dedicated to the defenders of the Soviet Union during World War II.

“I really like what they did with that memorial: the first part, which contains the names of all the people deported, shows the importance of remembering the past; the second part, the home garden with the apple trees, explains the importance of looking at the future. There is also a map of the places reached by the deported, and only when I stood in front of it, I realized how far my mother really went.”

The topic of the deportation was often discussed in Kallas family:

“My mother, my grandmother and my great-grandmother were in this cattle wagon for three weeks until the very last stop. It was like a slave market along the way, and nobody wanted two women with a small baby as workers.”

My mother, my grandmother and my great-grandmother were in this cattle wagon for three weeks: nobody wanted two women with a small baby as workers.

When Kaja’s father became the first president of the Bank Of Estonia, the Kallas family moved to Viimsi, a small, and nowadays wealthy, municipality about 15 kilometers northeast of the capital. Kaja lived there during high school and then moved to Tartu, a city renowned for its ancient university, founded in 1632.

“I first moved there in summer, and the city was completely empty. I was wondering if I did a mistake deciding to study there. Then, when autumn came, the students were back and the atmosphere changed completely”.

Tallinn and Tartu share a friendly rivalry, as the popular meme goes: “Tallinn thinks it’s Europe, Tartu thinks it’s ancient Greece”.

Politics was constantly discussed in the Kallas family, even during Soviet times. Her father’s later career, as Prime Minister of Estonia and then EU commissioner, did not inspire his daughter to begin with.

“It was really clear for me that I never wanted to go into politics: I wanted to be successful in a field in which none of my family member was already successful. They would have always compared me to my father, I didn’t want that. I wanted to be myself. So I studied law.”

Kaja was a teenager in the most interesting moment for Estonia: the restoration of independence from the Soviet Union, which started in 1991.

“When I started studying law, the new constitution and rules had just been written. When I was eighteen (1995, ed) I was already a trainee in a law firm and I kept working there during my studies. At twenty-seven, after I passed the bar exam, I became partner of a well-known law firm. And nobody could say that I achieved that because of my father”.

Nevertheless, she can’t avoid getting closer to the legislative power.

It was really clear for me that I never wanted to go into politics. They would have compared me to my father, but I wanted to be myself.

“I was writing opinion articles about current Estonian laws. If you’re a lawyer you use the law, but you can also see what is wrong with the law and I was suggesting changes.”

The turning point of her transition from law to politics was an event that couldn’t be more dependent on her father: his sixtieth birthday in 2008.

“I prepared a nice speech to celebrate him and in the audience there were lots of politicians from different parties. Many of them came to me saying: ‘You should move to politics, you would help us to innovate’. Back then, there were not many female politicians to look up to. It took me two years more to be persuaded, I accepted you can’t fight blood.”

In 2010, she joined the Estonian Reform Party, founded by her father in 1994. One year later, she ran in the political elections for the Harju and Rapla County constituency.

“It was my first election, I was a bit stressed, I needed some time by myself. When I turned my phone back on… it was full of messages: the e-votes were published immediately, before the paper votes were counted, and I already got three thousand votes. I wasn’t expecting more than three hundred in total; in the end, I got over seven thousand.”

The rest is history: Kallas became member of the Estonian Parliament (2011–2014), member of the European Parliament (2014–2018) and was elected leader of the Reform Party in 2018. After the ruling centre-right coalition collapsed in 2021, Kallas became prime minister, leading the country through a period of regional security threats, global energy instability, and growing geopolitical tensions.

She reached international attention after she vigorously confronted Angela Merkel at the European Council in June 2021.

How did it go, behind the scenes?

It was my first physical European Council, because before that we had remote ones, due to covid restrictions. France and Germany were pushing this idea of inviting Putin to the next summit. And I thought: “This is impossible”.

(Most likely it is my vivid imagination, but I see little flames appearing from her nostrils every time she pronounces the name of the Russian autocrat).

I was the only one fighting this proposal; all the other leaders were silent. Merkel already discussed the issue with Draghi and when it was his turn to speak, he just said: ‘I support France and Germany.’ And that was unusual, as Draghi always briefly explains why he takes a certain position, so I saw an opening there. I replied: “We agreed that we are not having high level meetings with Russia until they withdraw from Crimea, if we now invite them here, we will look ridiculous, it means our word doesn’t count.”

We agreed that we are not having high level meetings with Russia until they withdraw from Crimea

And some people dare say that EU politics is boring and emotionless…

It’s not. Merkel was so angry with me. And I felt so alone, Lithuania didn’t say a word. In the end, I said: “I am sorry, I don’t have a mandate to approve this and we all have to agree.” And the discussion continued until Draghi said: “But Kallas is right.”

A big endorsement. Did it feel like victory?

Not quite. After the Council, I went back to my people and I said: “My first European Council and I already destroyed our relationship with Germany and France. I am a failure as prime minister, but I just couldn’t agree to this”. On the next day, it was all different: Merkel was still angry with me, but the others respected me. Draghi told me: “You must have been a really good lawyer”. Later on, Merkel called me and invited me for lunch and she apologized and I apologized for being so stubborn.

After this European Council, Kaja Kallas quickly became known as one of Europe’s most forceful voices against Russian aggression; the media often portrayed her as a principled, unflinching leader from a small country with a deep historical understanding of Moscow’s imperial ambitions.

Her popularity, especially at home, took a hit at the end of 2023, when it was revealed that a logistics company partially owned by her husband (25% of shares) had continued doing business in Russia, despite Estonia’s sanctions. Kallas responded swiftly, stating that she had no prior knowledge of her husband’s business activities and maintained that no laws had been broken.

The scandal sparked calls for Kallas’s resignation, both from opposition parties and critical voices in the media. While she refused to step down, her husband announced he would sell his shares in the company to avoid further reputational damage. Despite the backlash, Kallas’ attitude towards Russia did not change; in February 2024, she was added to Kremlin’s list of wanted politicians over the removal of Soviet-era monuments.

Kallas continued to receive strong support in many European capitals and in June 2024, she was nominated to become High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. Her hearing in front of the European Parliament was praised by many: perfect English, very clear answers, few eurolingo moments.

Compared to her predecessor, the 78 years old Spanish socialist Josip Borrell, Kallas leadership has been direct, assertive and media-savvy. Her critics say she behaves like a prime minister and not as a representative of the Member States’ will. Meanwhile, the solution to the Russian invasion of Ukraine is still far from being found.

Is there anything you miss of the Soviet times?

Oh, no, no!

I always ask, it is hard for westeners to believe that the Soviet regime could go on for so long when everything was so bad.

In my position I travelled to all post-Soviet countries and I see in which conditions people live. But they’re still happy: if you have children and parents and friends you can live through any circumstances, you don’t complain about them. But if you give people better conditions, they will not miss anything of what they had.

A big thanks to RS and ML for the organizational help and to AH for the usual text review